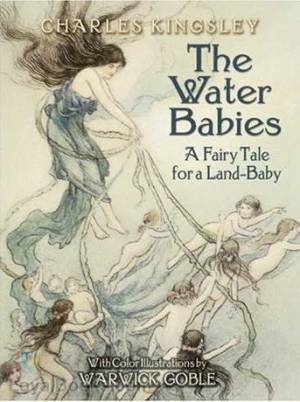

The Water-Babies: A Fairy Tale for a Land Baby, Charles Kingsley (1863)

The Water-Babies: A Fairy Tale for a Land Baby, Charles Kingsley (1863)

When I first read this as a child, I didn’t realize that it was one of the strangest books ever written. I do now. And the strangeness was heightened by the old edition I’ve re-read it in, because it came as a double volume that started with Kingsley’s The Heroes, or Greek Fairy Tales (1856).

No-one reading The Heroes would guess what awaited them in the second half of the book. The prose plods, the imagery is strictly conventional – “Then Aietes’ rage rushed up like a whirlwind, and his eyes flashed fire” – and Kingsley makes interesting stories dull. I quickly gave up when I tried to read them.

Maybe I was anticipating The Water-Babies too much. It starts almost conventionally, but it has an unconventional hero: “a little chimney-sweep” called Tom. He’s unwashed, unlettered, untaught, and unfairly treated by his master in “a great town in the north country”. But he accepts the hardships of his life, finds fun where he can, and thinks of “the fine times coming, when he would be a man, and a master sweep, and sit in the public-house with a quart of beer and a long pipe, and play cards for silver money, and wear velveteens and ankle-jacks, and keep a white bull-dog with one grey ear, and carry her puppies in his pocket, just like a man.”

That first long paragraph of The Water-Babies is already richer and more vivid than the whole of The Heroes. And the book hasn’t got strange yet. It starts to do so when Tom is taken into the country to sweep the chimneys of Harthover House, the grand home of the squire Sir John Harthover:

[It] had been built at ninety different times, and in nineteen different styles, and looked as if somebody had built a whole street of houses of every imaginable shape, and then stirred them together with a spoon.

For the attics were Anglo-Saxon.

The third door Norman.

The second Cinque-cento.

The first-floor Elizabethan.

The right wing Pure Doric.

The centre Early English, with a huge portico copied from the Parthenon.

The left wing pure Boeotian, which the country folk admired most of all, became it was just like the new barracks in the town, only three times as big.

The grand staircase was copied from the Catacombs at Rome.

The back staircase from the Tajmahal at Agra. […]

The cellars were copied from the caves of Elephanta.

The offices from the Pavilion at Brighton.

And the rest from nothing in heaven, or earth, or under the earth. (The Water-Babies, ch. 1)

That’s an early taste of the eccentric lists and juggling of ideas to come. Tom begins to sweep the chimneys of Harthover House, but accidentally comes down in the bedroom of the squire’s daughter as she lies asleep in bed. She’s the “most beautiful little girl Tom had ever seen”. And she’s completely clean. Then Tom notices someone else in the room: “standing close to him, a little ugly, black, ragged figure, with bleared eyes and grinning white teeth.”

He turns on it angrily, then realizes it’s his own reflection in a “great mirror, the like of which [he] had never seen before.” For the first time in his life, he understands that he is dirty. The knowledge startles and shames him, so he tries to flee up the chimney. But he upsets the fire-irons and wakes the little girl. She screams, thinking he’s a thief; and Tom’s adventures begin. He leaves the little girl’s bedroom by the window, climbing down the magnolia tree outside, and runs off.

Soon the whole house and its staff are chasing him, but he tricks them off his trail, “as cunning as an old Exmoor stag”, and makes off through a wood, then onto the hills of a moor. After the grand catalogue of architectural styles, Kingsley’s descriptions become detailed and naturalistic: “[Tom] saw great spiders there, with crowns and crosses marked on their backs, who sat in the middle of their webs, and when they saw Tom coming, shook them so fast that they became invisible.” But when he disturbs a grouse washing itself in sand, it runs off and tells its wife about the end of the world. Like Tom, the reader has entered a new world where animals think and talk.

But the truly big transformation is still to come. The sun is very hot as Tom climbs the limestone hills and starts down the other side. He grows thirsty and begins to suffer from sun-stroke. When he seeks help at a dame-school, he’s given some milk and a place to rest, but his head is ringing and he wants to be clean. He walks to a stream in a nearby meadow and bathes in it. Then he falls asleep in it:

Ah, now comes the most wonderful part of this wonderful story. Tom, when he woke, for of course he woke — children always wake after they have slept exactly as long as is good for them — found himself swimming about in the stream, being about four inches, or — that I may be accurate — 3.87902 inches long and having round the parotid region of his fauces a set of external gills (I hope you understand all the big words) just like those of a sucking eft, which he mistook for a lace frill, till he pulled at them, found he hurt himself, and made up his mind that they were part of himself, and best left alone. (ch. II)

He’s now a Water-Baby and can begin his amphibious adventures. As the title suggests, water is central to this book: it’s a protean, ever-changing medium, with the power to transform, transport and cleanse. And it has a lot in common with language, which is also protean and transformative.

So Kingsley plays with language as he describes water and its inhabitants. I thought he was making fun of scientific terminology – “3.87902 inches long and having round the parotid region of his fauces a set of external gills” is just the start – but apparently he was a friend of Charles Darwin and accepted Evolution. A lot of that goes on in this book: physical, intellectual and moral. Tom evolves from boy to Water-Baby, but he has a lot of bad habits to unlearn as he travels down the stream and the river into which it evolves. As part of his education, he talks with all kind of animals:

And as the creature sat in the warm bright sun, a wonderful change came over it. It grew strong and firm; the most lovely colours began to show on its body, blue and yellow and black, spots and bars and rings; out of its back rose four great wings of bright brown gauze; and its eyes grew so large that they filled all its head, and shone like ten thousand diamonds.

“Oh, you beautiful creature!” said Tom; and he put out his hand to catch it.

But the thing whirred up into the air, and hung poised on its wings a moment, and then settled down again by Tom quite fearless.

“No!” it said, “you cannot catch me. I am a dragon-fly now, the king of all the flies; and I shall dance in the sunshine, and hawk over the river, and catch gnats, and have a beautiful wife like myself. I know what I shall do. Hurrah!” And he flew away into the air, and began catching gnats. (ch. III)

Tom also meets wicked otters and snobbish salmon. Then he reaches the sea, realm of the ever-changing god Proteus, and things get even stranger. He talks with hermit-crabs and lobsters as he searches for other Water-Babies. Words and ideas run and swirl through the story like currents, and so do emotions. Tom experiences both joy and sadness:

And then there came by a beautiful creature, like a ribbon of pure silver with a sharp head and very long teeth; but it seemed very sick and sad. Sometimes it rolled helpless on its side; and then it dashed away glittering like white fire; and then it lay sick again and motionless.

“Where do you come from?” asked Tom. “And why are you so sick and sad?”

“I come from the warm Carolinas, and the sandbanks fringed with pines; where the great owl-rays leap and flap, like giant bats, upon the tide. But I wandered north and north, upon the treacherous warm gulf-stream, till I met with the cold icebergs, afloat in the mid ocean. So I got tangled among the icebergs, and chilled with their frozen breath. But the water-babies helped me from among them, and set me free again. And now I am mending every day; but I am very sick and sad; and perhaps I shall never get home again to play with the owl-rays any more.” (ch. IV)

That’s a description of an oar-fish, I think. When Tom finds the Water-Babies of whom it spoke, he completes his moral education under the guidance of two mother-fairies, the ugly Mrs. Bedonebyasyoudid and the beautiful Mrs. Doasyouwouldbedoneby. But the ugly can become beautiful: Kingsley was a Christian and this is a moralistic story too. The dirt that Tom has to lose is spiritual, not just moral and physical: he saw a crucifix in the little girl’s bedroom and didn’t know what it was.

But there’s too much going on in The Water-Babies for any simple reading of Kingsley’s aims. Or perhaps I’m saying that because I’m not a Christian. Either way, the book certainly isn’t conventional in its Christianity. Like C.S. Lewis’s Narnia or J.R.R. Tolkien’s Middle-earth, Kingsley’s world is big enough for non-believers. But it isn’t as coherent as Narnia or Middle-earth, or as easy to enter as Wonderland. That’s part of why The Water-Babies isn’t as famous or as widely read today. Lewis Carroll played with both logic and language; Kingsley plays with both life and language.

That’s what I like about this book. You’ll find vivid little naturalistic touches like spiders shaking in their webs and words like “Necrobioneopalaeonthydrochthonanthropopithekology”. If Charles Dickens and Lewis Carroll had collaborated on a book, it might have ended up something rather like The Water-Babies. And James Joyce would have been good as a collaborator too. I don’t know if he was influenced by The Water-Babies, but he could have been. He too was obsessed with language and water. Both of them are at the heart of this Fairy Tale for a Land Baby.