Iron Man: My Journey through Heaven and Hell with Black Sabbath, Tony Iommi, as told to T.J. Lammers (Simon & Schuster, 2011)

Iron Man: My Journey through Heaven and Hell with Black Sabbath, Tony Iommi, as told to T.J. Lammers (Simon & Schuster, 2011)

To understand why this book rocks, you just have to get back in Black. That is, turn to the index and the entry for

Ward, Bill

[…]

set on fire, 192-4, 369

Other bands go through blues periods or heroin periods or prog-rock periods. Black Sabbath went through a setting-their-drummer-on-fire period. If Led Zeppelin were rock-gods, then Black Sabbath are rock-goblins. Which is one reason I prefer them to Led Zep. Another reason is their music: it’s much more inventive and much less pretentious, in my opinion. You can’t imagine Led Zep setting their drummer on fire and you can’t imagine them recording a song called “Fairies Wear Boots” either. If Led Zep had never existed, it’s hard to see that rock music would be much different today. If Black Sabbath had never existed, rock music might be a lot different. It might also be a lot better, in some people’s opinion, because Sabbath were central to the creation of heavy metal. But their doomy, tolling sound owes something to chance – the unhappy chance of Iommi losing the tips of his right fingers on his last day at work in a factory in Birmingham. He thought it had ended his nascent career as a guitarist, but he found a way to use home-made “leather thimbles” to protect his reconstructed fingertips. All the same:

I’m limited because even with the thimbles there are certain chords I will never be able to play. Where I used to play a full chord before the accident, I often can’t do them now, so I compensate by making it sound fuller. For instance, I’ll hit the E chord and the E note and put vibrato on it to make it sound bigger, so it’s making up for that full sound that I would be able to play if I still had full use of all the fingers. That’s how I developed a style of playing that suits my physical limitations. It’s an unorthodox style but it works for me. (ch. 6, “Why don’t you just give me the finger?”, pg. 24)

Iommi needed determination and willpower to overcome the accident and both are apparent in the photo-section. He looks, to put it simply, like a hard bastard. “Iron Man” is a good name for this autobiography and it isn’t surprising that Ozzy Osbourne was frightened of him. Iommi has been the engine of Black Sabbath in more ways than one: he writes the riffs and rights the riff-raff and he’s been the only ever-present in the band. I wonder how much his music and his menace are owed to genetics: he was born in Birmingham, but both his parents were of Italian descent and Iommi looks distinct from the native Brits Ozzy Osbourne, Geezer Butler and Bill Ward, who have lighter hair and milder eyes. Once you’ve seen the photos, the dynamics of the band should come as no surprise:

We also had some bloody laughs there [in Miami during the recording of Technical Ecstasy (1976)], especially when we played jokes on Bill. He would never allow the maids in to clean his room. One day we got a big load of this really horrible, smelly Gorgonzola cheese, and while somebody kept him talking I sneaked into his room and piled it under the bed. [L]ater I came in again and the smell was atrocious. I went: “Phew, Bill, what’s that smell?”

“I don’t know what it is, it must be my clothes.”

Bill is a dirty bugger; he’d pile his filthy clothes in a corner.

“When are you going to clean them?”

“I will, yeah.”

He never sussed out the cheese under the bed. It smelled absolutely vile. He actually started smelling like cheese himself. (ch. 40, “Me on Ecstasy”, pg. 156)

Bill Ward was the butt of the band, as the bassist Jason Newsted was in Metallica. Like Newsted, Ward left the band that made him famous, but unlike Newsted he returned and is still there. He was lucky: he might have left permanently after the final “set the drummer on fire” incident. It put him in hospital and could have killed him, Iommi says in chapter 48, “Ignition”. Or T.J. Lammers, his ghost-writer, says on his behalf, anyway. I was a bit disappointed to see the autobiography was an “As Told To”, but it’s probably for the best, because Iommi admits he had a poor education. And you quickly forget the ghost-writing once you start reading. Lammers doesn’t try to get literary or high-flown and Iommi seems to be chatting in a down-to-earth, Brummie way about his decades in one of the world’s biggest and most influential rock-bands. One of the loudest too. Why is a song on Born Again (1983) called “Disturbing the Priest”? Because they recorded the album in a studio called The Manor in the Oxfordshire countryside and the noise prompted a petition from the neighbours, which was delivered by the local priest. Iommi goes on to explain how the album was heavy metal in more ways than one:

In those days you had to make your own effects. Bill made this particular “tingngng!” sound on “Disturbing the Priest”. He got this by hitting an anvil and then dipping it into a bathtub full of water, so that the “tingngng!” sound slowly changed and faded away. It took us all day to do that, because trying to lower the anvil gradually into the water was a nightmare. It took two people on one end and two more on the other to lower it, with somebody else hitting it. It was so heavy that we couldn’t speak or anything, just sort of nod to each other… All this to create one “tingngng!”, which nowadays you can get from a computer in seconds. (ch. 56, “To The Manor Born”, pg. 224)

So the anvil was a handful, but Iommi doesn’t describe any other sweaty activities. He keeps things clean: chapter 24 describes fishing “out of the window” at the Edgewater Hotel made famous in Hammer of the Gods (1985), but no groupies are introduced to fish in unusual ways. Elsewhere he talks about drugs a fair bit, but there’s more about the music and the menacing. I’d include the jokes and pranks under that last heading. This is the funniest rock bio I’ve ever read, but I’m sure it was less funny to be on the receiving end of Iommi’s alpha-male domineering. Setting Bill Ward on fire or abandoning him, blind drunk, on a boating-lake or park-bench was on the simpler, more spontaneous side, but he also convinced Martin Birch, the superstitious producer of Heaven and Hell (1980), that he was being jinxed with a voodoo doll:

I loved it. I really lived on it. I was looking forward to going in the next day, just to wind him up some more. Martin changed from being this confident chap to being a nervous wreck, going: “What’s happening, what’s going on?”

“Nothing, nothing.”

I got the doll out again and he said: “You’re sticking pins in it! It’s me, isn’t it? That’s me!”

[…] Fantastic, it was a real gem and it lasted the entire recording session. We never told him. He’ll read this book and go: “The bastard!” (ch. 47, “Heaven and Hell”, pg. 190)

In the next chapter Iommi is nearly barbecuing Bill Ward, but a few chapters later, he’s having to rescue someone else from dangerous jokes. On the Born Again tour, whose Stonehenge stage-set inspired a famous scene in Spinal Tap (1984), Sabbath’s then manager Don Arden decided to re-create the “Devil Baby” on the album’s cover. So he hired a “midget in a rubber outfit” to leap off the Stonehenge columns and flash his eyes at the audience before the show started:

The midget was a bit of a pop star, because he’d been one of the little bears in Star Wars. Ozzy at the time also took a midget out on the road; I think he called him Ronnie. I don’t know who had the first one, really. It became a thing. Midgets were in demand. But we had the famous midget because ours was in Star Wars. (ch. 57, “Size Matters”, pg. 233)

But the crew didn’t like the midget’s references to his fame and started to play tricks on him:

We finally decided it was best for all parties concerned if he left, especially after the crew decided to put the lights out on him at the very moment he jumped from the columns onto the drum riser. He went: “Aaaaaah!”

Splat!

He caught the edge of the drum riser and nearly broke his neck. Meanwhile, we were backstage waiting to come on and it just blew the show. We said: “That’s it, he’s gone!”

They would have killed him if we hadn’t fired him. (Ibid., pg. 233)

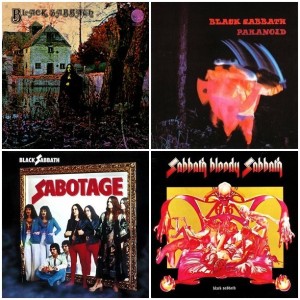

You don’t get midgets in Hammer of the Gods, to the best of my recollection. It’s another reason to prefer Hammer of the Goblins: this book is better-written and there’s much more humour in the Sabbath story. If it sometimes has a dangerous edge, that makes it like life. Also like life is Sabbath’s music: some is good and some is risible. Their album covers run the gamut too: Black Sabbath (1970) and Sabbath Bloody Sabbath (1973) are good, Paranoid (1970) and Sabotage (1975) are risible. But Paranoid contains some of their best music and is named after their most famous song. This was actually a filler for the album after the producer Rodger Bain said to Iommi: “We don’t have enough. Can you come up with another song? Just a short one?” (ch. 18, “Getting Paranoid”, pg. 73)

Two good, two bad — click for larger image

The others “popped out for lunch”, Iommi came up with a riff, then Geezer came up with the lyrics, though Iommi says that he and Osbourne probably didn’t know what “paranoid” meant at the time: “Ozzy and me went to the same lousy school, where we certainly wouldn’t be around words like that” (pg. 74). This uncharacteristically short and fast song brought them their greatest success, including an appearance on Top of the Pops. You can expect the unexpected with Black Sabbath. Also unexpected is that they’re all still around, despite the drugs and the dangerous jokes. Friends of Iommi’s, like John Bonham, Ronnie Dio and Cozy Powell, are no longer around, but he reminisces about them here and about his still-living friends and admirers. For example, he wins tributes on the back cover from Brian May, Eddie Van Halen and James Hetfield. I think the tributes are well-deserved. Iommi’s success is based on inventing music and inspiring metal, not igniting musicians or employing midgets. It’s the latter that make this book so entertaining and memorable, but no-one would want to read it if it hadn’t been for the music:

I thought “Zero the Hero” [off Born Again] was a good track and apparently I’m not the only one who likes it. When I heard “Paradise City” by Guns N’ Roses I thought, fucking hell, that sounds like one of ours! Somebody also suggested that the Beastie Boys might have borrowed the riff for “(You Gotta) Fight for Your Right (To Party!)” from our song “Hot Line”… I have a habit of keeping my riffs; I’ve got thousands of them. You know a riff is good when you play it and it gets to you. You just feel a good riff… I found that while I’m still able to keep writing them, I usually don’t go back to the old ones, so I’m only getting more and more. Maybe I should sell riffs! (ch. 56, “To the Manor Born”, pg. 224)

But that is what he has been doing throughout his career: selling riffs and shaping rock. He’s earnt his star on Birmingham’s “Walk of Fame” and deserves the respect he’s paid by everyone from Henry Rollins to Lemmy out of Motörhead. And even if you don’t like his rock’n’roll, you may still find yourself rocking with laughter at his stories.

Elsewhere other-posted:

• More Musings on Music

Read Full Post »

Watch You Bleed: The Saga of Guns n’ Roses, Stephen Davis (Michael Joseph 2008)

Watch You Bleed: The Saga of Guns n’ Roses, Stephen Davis (Michael Joseph 2008)