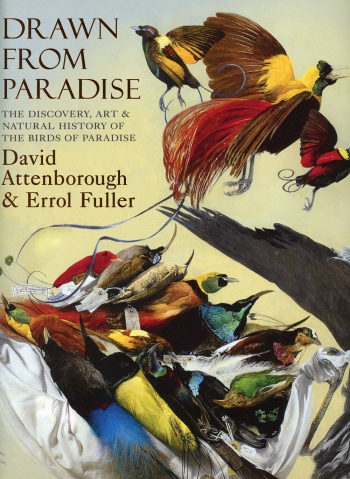

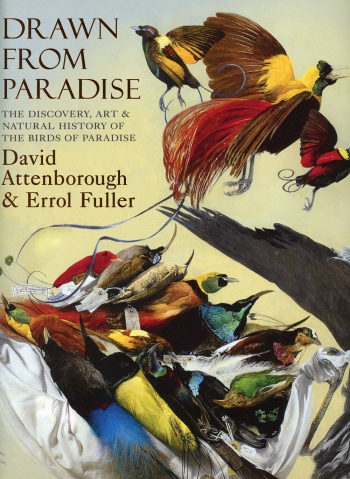

Drawn from Paradise: The discovery, art and natural history of the birds of paradise, David Attenborough and Errol Fuller (Collins 2012)

Drawn from Paradise: The discovery, art and natural history of the birds of paradise, David Attenborough and Errol Fuller (Collins 2012)

A book about feats for the eyes that also is a feast for the eyes. The second set of eyes are human; the first are avine – specifically, the eyes of female birds of paradise. The gorgeous plumage of the males has been created by female preference over many generations. The more attractive a male’s feathers and the more energetically and skilfully he displays, the more likely he has been to mate and leave offspring. As the most attractive males in each generation are selected, so the features that make them attractive grow ever more exaggerated, even – or especially – if they become a handicap in escaping predators and so on.

Darwin called this “sexual selection” and it’s most famous in the peacock. Peahens are drab and inconspicuous by comparison, but they are the driving force for the spectacular feathers of the male. If peacocks didn’t exist, would any artist have been able to create them? I don’t think so. The same goes for the birds of paradise: it’s not just their beauty and extravagance that are astonishing. So is their variety. Some have golden feathers, some have scarlet, some have celestial blue. Some have plumes, some ruffs, some sprays, some wires and some “flank feathers” that rise “to form a perfect ellipse”, framing the male’s head during courtship (ch. 6, “The Sicklebills”, pg. 142).

That’s the brown sicklebill, Epimachus mayeri. The superb bird of paradise, Lophorina superba, does something even stranger, raising a cape of feathers on its back to create a kind of cone around its head, in the shadow of which two white head-feathers glimmer like eyes. But it wasn’t until artists saw these birds in the wild that they knew precisely how to represent them. Before that, they’d used guesswork and inevitably got many things wrong. For a long time, as Attenborough describes, artists were working from dead specimens, sometimes traded several times before they reached Europe and sometimes lacking their wings and feet. This gave rise to the legend that the birds floated rather than flew, living permanently in the sky till they died and fell to earth. Hence the name “birds of paradise”:

In 1522 the first of many, many bird of paradise plumes arrived in Europe. Within just months they attracted the attention of a celebrated artist, Hans Baldung Grien. His picture may have been a comparatively flimsy affair, but it began a tradition among artists that has continued to this day. The list of artists who have felt compelled to paint or draw birds of paradise is studded with some illustrious names: Brueghel, Rubens, Rembrandt, Millais. Then there are men who actually specialised in painting birds: [Jacques] Barraband, [Josef] Wolf, [William] Hart, [John] Gould, [John Gerrard] Keulemans. And, of course, there are modern painters. Walter Weber produced a series of iconic images for The National Geographic magazine during the early 1950s. William T. Cooper illustrated two major monographs on birds of paradise, and Raymond Ching is known throughout the world for his poetic and highly charged paintings. (Introduction, pg. 32)

The work of these artists illustrates the book. There are no photographs, just paintings, drawings and engravings from the six centuries during which Europeans have been fascinated and dazzled by the Paradisaeidea. Errol Fuller, the co-author of the book, is one of the artists. He’s a skilful painter, but he has to be: birds of paradise are challenging subjects, the visual equivalent of a complicated piece for violin or piano. An artist has to have full command of colour and line. The artists here do: you can almost smell the jungle in some modern paintings.

Jacques Barraband, Petit oiseau de paradis

But that realism is the influence of photography and of personal observation. The Frenchman Jacques Barraband (1761-1809) never got to Papua New Guinea or northern Australia, so he never saw the living birds, but he remains one of the great paradiseans, able to bring dead specimens to life on canvas. The biographical section at the end of the book, describing “People Associated with the Discovery and Visual Representation of Birds of Paradise”, says this:

Despite the incredible beauty of his images, and the great influence they have had, comparatively little is known of Jacques Barraband and it has not proved possible to find a portrait of him. He was the son of a weaver, and it seems he worked originally as a tapestry designer at Gobelin’s, and later turned his hand to decorating porcelain at the famous factory in Sèvres. (pg. 236)

So we know he existed, but we don’t have an image of him. The opposite applies to some birds of paradise: we have images, but don’t know whether they ever existed. Some paintings and drawings are mysterious. Are they are invented or based on real specimens that are now lost? Birds of paradise often hybridize, adding more phantasmogoric variety to the family, and a few species may have gone extinct or be awaiting re-discovery.

Those are tantalizing prospects, but the biological interest of this book isn’t confined to birds. The biographical section at the back contrasts with what’s gone before. Birds of paradise come in many colours and shapes, but the “People Associated with” their “Discovery and Visual Representation” are overwhelmingly white males of northern European ancestry. They’re the ones who have created the beautiful art and run the enormous risks. New Guinea has always been a dangerous place, with its fast rivers, mountainous terrain, violent tribes and tropical diseases. That’s why it attracted one of the twentieth century’s greatest adrenalin-junkies:

Adventurer, bar-fly, beachcomber, boxer, brawler, drifter, entertainer, freedom fighter, lover, platypus and bird fancier, prospector, self-confessed thief, sailor, writer, Hollywood icon, Errol Flynn [1909-59] packed every conceivable human activity into his whirlwind tour through life. He starred in almost 60 films, wrote two novels and an autobiography, before dying at the comparatively early age of 50 from the effects of a totally worn-out body. (pg. 240)

I was surprised to find Errol Flynn here, but his presence and the quote about collecting birds of paradise from his memoir My Wicked, Wicked Ways (1960) make the book even stranger and even more satisfying to read. White men like Flynn are as spectacular for their achievements as male birds of paradise are for their plumage. Perhaps sexual selection explains both sets of phenomena. Certainly some kind of evolution does, because genetics are responsible for the feats of both. There is much more to this book than birds, but phantasmagoric feathers are why it’s such a feast for the eyes.

Read Full Post »