A Forger’s Tale: Confessions of the Bolton Forger, Shaun Greenhalgh (Allen & Unwin 2017)

A Forger’s Tale: Confessions of the Bolton Forger, Shaun Greenhalgh (Allen & Unwin 2017)

Was I was one of the many people fooled by the Bolton Forger? I think so, because a few months ago I read a book on Leonardo da Vinci that contained an attractive profile of a young woman. I liked it and even thought of finding it online and putting it on Overlord-of-the-Über-Feral.

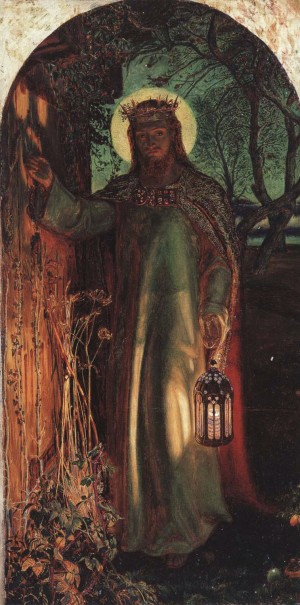

I’m pretty sure that the same drawing, entitled La Bella Principessa, opens the photo-section of this fascinating and well-written autobiography. The caption underneath runs:

I saw this drawing in Milan in 2015 and despite all the frenzy in the press, it is my work of 1978. Although it looks to have been gone over or ‘restored’ by a better hand than mine. But, like me, no Leonardo!

In his final chapter, “Postscript”, Shaun Greenhalgh (pronounced Green-alsh or similar) gives more details. He says that he made the drawing in imitation of Leonardo, then sold it “for less than the effort that went into it to a dealer in Harrogate in late 1978 – not as a fake or by ever claiming that it was something it wasn’t.” More than 30 years later, he learned that his drawing had risen higher in the world than he could ever have guessed:

I received [an art book from an anonymous donor and] the picture on the cover was immediately familiar, but better-looking than I remembered it. […] [The] title [of the drawing] was rather grand and pompous – La Bella Principessa – the beautiful princess. Or, as I knew her, ‘Bossy Sally from the Co-Op’. (pg. 354)

From the sublime to the ridiculous! The Co-Op is a supermarket chain in northern England. Greenhalgh continues:

I drew this picture in 1978 when I worked at the Co-Op. The ‘sitter’ was based on a girl called Sally who worked on the check-outs in the retail store bolted onto the front of the warehouse where I also worked. Despite her humble position, she was a bossy little bugger and very self-important. If you believe in reincarnation, she may well once have been a Renaissance princess – she certainly had the attitude and self-belief of such a person.

You see the girl in the drawing differently when her label changes. But the drawing itself hasn’t changed. Now that I think back on my first sight of it, I remember being half-aware that it was remarkably clear and bright by comparison with the other art in the Leonardo book. It definitely stood out, but I didn’t suspect anything. After all, it was in a book by an expert on Leonardo, so I accepted its attribution without question.

And so, without knowing it at the time, I had an important lesson in the way art often works. Our appreciation of it can be affected much more than we might like to think by the labels and reputations that go with it. Greenhalgh says here more than once than we should enjoy art without worrying about whether it’s genuine or not. And what is “genuine” anyway? That’s one of the fascinating questions raised by this book and by the phenomenon of forgery in general. Here’s more of what he says about the drawing:

I’m a bit unsure how to talk about this because the book was written by an eminent Oxford professor and must have been quite an effort. I don’t want to ruffle any feathers or cause problems but I nearly swallowed my tongue on reading of its supposed value – £150 million! It would be crazy for any public body to pay such a sum. So I feel the need to say something about it.

He goes on to describe how he created the drawing and made it look old. It was a good effort but he says there are “umpteen reasons for not thinking this drawing to be by Leonardo.” (pg. 357) One of the most important, for him, is that it isn’t skilful enough: “I couldn’t match how Leonardo would have rendered it [a section of cross-hatching]. But I have a good excuse. He is he and I’m just me.”

Well, Shaun Greenhalgh isn’t impressed by Shaun Greenhalgh, but lots of other people have been. If you read this book, you’ll probably join them. He tells the remarkable story of how an apparently ordinary lad from the Lancashire town of Bolton fooled the art world again and again with work in a great variety of mediums and styles. Sometimes he meant to fool people and sometimes, as with La Bella Principessa, he didn’t. And he says he’s sorry that Bolton Museum, “my favourite childhood place”, was duped by a “15 minute splash of light and colour” he’d done “in the style of Thomas Moran”, an American artist originally born in Bolton.

The watercolour is reproduced in the photo-section, labelled “© Metropolitan Police”, because Scotland Yard – or “the Yardies” as Greenhalgh disdainfully calls them – now have a lot of what he’s created. They raided his home, carried away much of the contents, then slowly got around to prosecuting him. In the end, he got four years and eight months in jail for his artistic endeavours. The art-critic Waldemar Januszczack condemns the length of that sentence in the introduction. Januszczack was someone else fooled by the Bolton forger. In his case it was a Gauguin Faun “[d]one in three parts and authenticated by the Wildenstein Institute of Paris”. Januszczack waxed lyrical about the faun in a Gauguin biography he did for the BBC, but says that “[i]nstead of hating Shaun Greenhalgh for fooling me, I immediately liked him for pushing my button and being a clever rogue.” (Introduction, pg. 4)

Greenhalgh wouldn’t agree that he’s either clever or a rogue, but he’s definitely wrong about the first thing, at least. He’s a self-taught expert on a dazzling range of art from a daunting stretch of centuries. Or millennia, rather, because his forgeries included an attractive “Amarna Princess” in alabaster, supposedly from the reign of the Pharaoh Akhenaten in the 14th Century BC. Like many of his other works, the princess was coveted by an “expert” who thought he could get it for much less than it was apparently worth. After all, the statue was being offered for sale by a family of thick northerners – Greenhalgh and his parents – who had no real idea of what it was. In fact, they had a much better idea than the expert – or the experts, rather, because the “Amarna Princess” was probed and pondered for months. Greenhalgh never expected it to withstand the scrutiny, but: “In late October 2003, we were paid half a million for the Amarna Princess, less taxes. So $440,000.” It ended up in Bolton Museum again and Greenhalgh says again that he wasn’t comfortable about that and didn’t touch most of the money.

And is he still trying to assuage his conscience when he insists the Princess clearly wasn’t pukka?

The first problem with the Amarna figure was that it was not done to a proper proportion, something fundamental in all ancient Egyptian sculpture, even with the radical designs of the court of Akhenaten. […] The left arm, or what’s left of it, was cut ovoid in section, which is again un-Egyptian. Part of the robe extending into the negative space to the figure’s left is also totally wrong. […] One other mistake about it was that I put a ‘contrapposto’ into the torso that was totally out of place. That’s the slightly slouchy pose you first see in Greek art of the classical period, post-fifth century BC. It isn’t found at all in Egyptian sculpture. (pg. 346)

Maybe he’s trying to assuage his conscience or maybe he’s re-living his triumph over the experts. Or maybe he’s doing both. Whatever it was, his next major forgery, a bas-relief of an Assyrian priest, was meant for the British Museum down south. And this was a forgery too far. The experts rumbled him this time and the police came knocking. Then he began a slow legal journey towards conviction and custody. Prison is where he wrote this autobiography, but he doesn’t devote much space to it. Instead, he describes how an apparently ordinary lad from Bolton, born in 1960, acquired such a love for and knowledge of art from all over the world and right through history, whether it’s ancient Egypt, Renaissance Italy or Mayan Mexico. Unlike most of us, though, when Greenhalgh liked the look of something he wanted to make something like it for himself. And he wanted it to be as authentic as possible. That’s why he learned about the chemical composition of Roman metalwork and Chinese porcelain.

Most art experts learn through their eyes, by looking at art and reading about it. Greenhalgh did that, but he stepped into a third dimension because he learnt with his hands too. And he stepped into a fourth dimension, because he learnt about the role of time and patience in artistic creation. By doing all that, he won insights that few others possess. As he says: “I’ve always found it strange that art, unlike most professions and trades, has as its experts and explainers people who can’t do that of which they speak.” (pg. 311) For example, how many Egyptologists know what it’s like to carve a statue for themselves? Very few. But Greenhalgh does and he acquired even greater respect for ancient sculptors by discovering how difficult the stone they worked with was. But that’s the way he wants it: “I like to do things that are difficult. Easy isn’t a challenge, is it?” (pg. 293)

However, he discovered that the effort he put into some forgeries was wasted, because art-dealers often didn’t know what to look for. And often didn’t care. They took what they thought they could sell. At other times, they did care what they were buying – a lot. But they tried hard to conceal their interest, because they thought they had a gullible and ignorant seller to rip off. A lot of Greenhalgh’s work is still out there, sailing proudly under false colours. He’s seen some of it but kept shtum, he says. That’s partly because he doesn’t want to spoil the new owners’ enjoyment and partly for his own protection. He doesn’t want to go back to jail.

But his first and so far only stretch in jail was worth it in one way, because it produced this book. He says that “A good faker, just like a good artist, has to be a close observer.” (pg. 296) And there’s a lot of close observation here about both art and life. Greenhalgh lost his wife-to-be when she died of a brain tumour and says that marriage would have taken him down a different path. He would have stopped forging and never gone to jail. Nor would he have written A Forger’s Tale. That makes you look at the book in a new way. Literature is even more about perspective and labels than art is. A clever writer like Michael Connelly knows that, which is why he wrote a crime novel, Blood Work, with such a clever twist at the end that I re-read it at once, marvelling at the way the text had suddenly changed.

A Forger’s Tale isn’t a novel and I won’t be re-reading it immediately. But I would like to read it again sometime. Greenhalgh isn’t a professional writer but he obviously could have been if his inclinations had lain that way. As it is, the occasional naivety of his prose adds to the appeal. He’s an ordinary lad with some extraordinary talents for what he’d call imitation, not creation. And he has extraordinary knowledge too. There is a lot of information here about art and the brief definitions in the glossary make me think of the Latin phrase Leonem ex ungue – “You can recognize the lion by his claw”. Here’s Greenhalgh’s definition of “Reducing atmosphere”, for example: “An atmospheric condition need to achieve specific ceramic effects, in which oxidation is prevented by the removal of oxygen.”

But any self-respecting ceramics expert could tell you what a “reducing atmosphere” is. Greenhalgh knows more: how to create one. Here’s his top tip:

You can use any combustible material [in the kiln], but most burn with some debris landing on the pot, causing imperfections. Mothballs splutter and vaporise instantly, starving the kiln of oxygen. (pg. 294)

So there’s everything here from mothballs to the Mayans, from lanxes of silver to Lowry of Salford. Crime captures life in all kinds of ways and the forger Shaun Greenhalgh has some very interesting things to write about.

Read Full Post »