A further exclusive extract from this soon-to-be-published key compendium of core counter-culturalicity…

[…]

Miriam Stimbers: How did you meet David Slater [simul-scribe of seminal snuff-study Killing for Culture]?

David Kerekes: Well, it’s a fairly complicated story. In the Gypsy community we’ve always felt a close affinity with other oppressed minorities and we do our best to watch their backs. In 1982 or thereabouts, I was part of a Gypsy crew who lent a helping hand to a gay brothel in Stockport that was having a few problems with homophobic neighbours. My blood still boils when I think about it, to be honest. Totally out of order, the fucking neighbours were. I mean, the brothel was discreet, the clients were no bother to anyone, but these homophobes thought they had the right to stick their fucking noses in and disrupt the brothel’s business, hassle the clients, stuff like that. Fucking cunts. Anyway, to cut a long story short, me and the rest of the Gypsy crew sorted the neighbours out and then the proprietor of the brothel asked us if we’d like blow-jobs on the house, like, to thank us for our help, even though we hadn’t done it out of any thought of reward. I mean, it was just solidarity with a fellow minority, the sort of thing the Gypsy community has always been passionate about.

Miriam Stimbers: And you said yes to the blow-jobs?

David Kerekes: Well, me and a couple of my mates in the crew did. I’m always up for a new experience, as it were! And that’s how I met Dave Slater. ’Coz he was working in the brothel, as one of the rent-boys.

Miriam Stimbers: And he gave you the free blow-job?

David Kerekes: Yeah. And it was a fucking good one too. Not the best I’ve ever had, like, but in the top twenty, easily.

Miriam Stimbers: And you got chatting and discovered your shared passion for corpse-contemplation?

David Kerekes: Well, it’s natural you should think that, but no, not right then. Not on that first occasion. Dave didn’t say much, just got down to work, as it were. But as I said, it was a fucking good blow-job, so about a fortnight later, when I was in the Stockport area on business and had an hour or two to kill, I popped in at the brothel and asked for another one off him. Another blow-job, I mean, off Dave. I was ready to pay the going rate, like, but the proprietor recognized me at once and said it was on the house again.

Miriam Stimbers: And this time you got chatting with Dave Slater?

David Kerekes: Exactly. We got chatting after he’d given me the blow-job and discovered our shared passion for corpse-contemplation, as you so nicely put it. And the next time Dave was over in Liverpool, he got in touch and we had a few pints. It all sort of blossomed from there. We started meeting regularly to watch death-film and corpse-vids together. Most times, Dave would give me a blow-job at the end of the session. I mean, you build up a lot of tension watching corpse-vids, so a blow-job’s just the thing to unwind with. Very relaxing. And sometimes he’d give me a blow-job during the session too, if he noticed I was getting tense as I contemplated a particularly fine corpse or watched a particularly abhorrent death-scene, like. It was fucking funny at times, Dave trying to watch the screen at the same time as he had a nob in his gob!

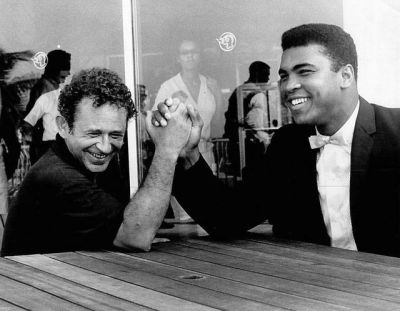

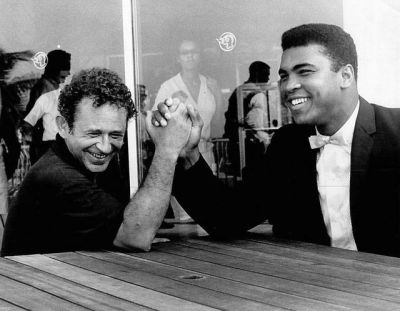

Warming up for corpse-contemplation: Kerekes (right) and Slater (left)

Miriam Stimbers: And that’s how you came to write Killing for Culture?

David Kerekes: Yeah. Out of tiny oaks tall acorns grow! If me and my Gypsy mates hadn’t helped out that gay brothel in Stockport, I’d probably never have met Dave and probably Killing for Culture would never have been written. I’d had something in mind along those lines, but Dave’s help really was invaluable. Not just his knowledge and his contacts, but his very special relaxation techniques! I estimate that I received about two hundred blow-jobs, maybe two-fifty, off him in the course of research. When I saw that first review calling it a “seminal snuff-study”, I thought, “Little do you fucking know!” Dave was always on at me to bum him too, but I didn’t fancy that. I mean, obviously, I’m not homophobic or owt, but bumming a bloke is a big step up from getting a blow-job off him. But he still kept on at me to bum him.

Miriam Stimbers: Did you ever give in?

David Kerekes: Well, I used to say to him, “Dave, I’ll bum you after we’ve seen a snuff-movie together!”

Miriam Stimbers: So have you ever bummed Dave Slater?

David Kerekes (laughing): Well, I’ll say this, like. I’ve bummed Dave Slater as many times as I’ve seen a snuff-movie!

Miriam Stimbers: And how many times have you seen a snuff-movie?

David Kerekes (laughing again): As many times as I’ve bummed Dave Slater!

[…]

Miriam Stimbers: Who would you say has been the most important influence on your life?

David Kerekes: People often ask me this and, you know, they expect me to say that it was William Burroughs or Immanuel Kant or Sam Salatta or someone like that. And yeah, they have all been very important influences on me, but the most important influence on me was someone else. Not anyone famous, but someone very, very influential nonetheless.

Miriam Stimbers: Who was it?

David Kerekes: It was my Mom, Mirima Kerekes. People often say to me that they find me an unusually honest and ethical person, which is obviously a nice thing to hear, don’t get me wrong, but I take absolutely no fucking credit for it. It’s all down to my Mom. She brought me up to be passionate about three things. First, pride in my Gypsy heritage. Second, strict adherence to a painfully honest ethical code. Third – and I’ll put it in her own words, because I can hear her saying it to me now – “Don’t never never never act like a communist, Davy, because that would be like spitting in your poor Momma’s face.” And I’ve done my fucking best, I hope, to keep those three things at the forefront of my mind during both my working life and my private life.

Miriam Stimbers: Just to explain for people who don’t know – your mother was a refugee from communist Romania, right?

David Kerekes: Yes, absolutely right. She left Romania in the 1950s after the Russian invasion. Fled from there, rather, just ahead of the fucking tanks and the firing-squads. And she wasn’t a fan of communism, to put it mildly!

Miriam Stimbers: And what would, quote, acting like a communist, unquote, entail?

David Kerekes: Basically, she meant any kind of behaviour that violated individual autonomy, that placed the collective above the individual. The sort of fucking thing you saw all the time under communism, most obviously with the secret police. You know, the KGB in the Soviet Union, the Stasi in East Germany, the Securitate in Romania, and so on.

Miriam Stimbers: Torture, rigged trials, slave-labour camps, things like that?

David Kerekes: Yes, obviously that kind of thing, but other stuff comes under it too. I mean, if you think of the Edward Snowden revelations, the NSA over in the States and GCHQ here in the UK are behaving like communists, by my Mom’s criteria.

Miriam Stimbers: Surveillance, spying, treating the entire population as suspects?

David Kerekes: Exactly. After her experiences in Romania, my Mom hated that kind of thing, absolutely fucking hated it. And if I ever participated in anything like that, then I would be, in her words, “spitting in your poor Momma’s face.” So I don’t participate in it. Full stop.

[…]

Interview extract © David Kerekes / Dr Miriam B. Stimbers / TransVisceral Books 2017