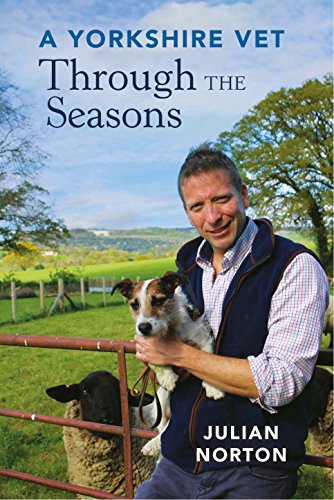

A Yorkshire Vet Through the Seasons, Julian Norton (Michael O’Mara 2017)

A Yorkshire Vet Through the Seasons, Julian Norton (Michael O’Mara 2017)

One of my big reader’s regrets is that I never read any of the James Herriot books until I was an adult. I enjoyed them a lot and have re-read them several times, but I’d’ve enjoyed them even more as a kid. Herriot was a skilful writer able to evoke all the sights, sounds and smells of his life as a rural vet in 1930s Yorkshire. And then 1940s and ’50s Yorkshire and beyond. His writing had humor and depth and was full of memorable characters, human and animal.

Julian Norton was inspired to become a vet by those books and the television series based on them. And after he followed in Herriot’s veterinary footsteps, he became famous like Herriot too. Except that his fame came the other way around: first a TV series, then a string of best-selling books based on the series. I’ve never seen the TV series, but I’ve started to read and enjoy the books. Julian Norton has a lot of James Herriot’s gift for narrative, anecdote and humor. He’s as likeable on the page as he must be on the screen. But you don’t get animal encounters like this in the Herriot books:

Fields that once were home to over a hundred black and white cows were filled with elegant, long-legged and long-necked creatures whose eyelashes rivalled those of their bovine predecessors and whose fleeces were many times softer than those of the sheep whose fields they adjoined. […] On my first visit I found that, quite unlike sheep, which would immediately tend towards fear and flight, these curious creatures would come up and investigate whatever was going on. They had no malice and radiated a calm serenity, both in their demeanour and also the gentle noises they made. Standing in a field of alpacas, I discovered, was a calming, tranquil experience. – “Miscellaneous Creatures”, pp. 187-8

That’s from the “Summer” section of A Yorkshire Vet through the Seasons, which begins in “Winter” and ends in “Autumn”. The variety of weather he encounters, from snow and sleet to sun and mist, is surpassed only by the variety of animals. There are a lot of them here, from the everyday to the exotic. There’s a lot of science too. Fortunately, Norton wears his learning lightly, which is just as well, because he has a lot of it: it’s harder to become a vet nowadays than a doctor. Competition for places at veterinary school is more intense and academic demands are higher, thanks first to James Herriot and then to the vets who followed his lead and wrote about their lives as a vet or allowed cameras to film them at work. But being a vet has always been harder, both physically and intellectually, than being a doctor. On the one hand, farming vets are routinely injured and sometimes killed by their sick patients, and have to attend them in all kinds of weather and places. On the other, there’s a much greater variety of anatomy and ailment to learn. Particularly nowadays. And a sick animal can’t say where or how it hurts, of course.

So there’s often a puzzle to be solved at the beginning of a vet’s meeting with a new patient. What’s wrong with this animal and how do I treat the problem? James Herriot asked that question every day and now Julian Norton is asking it too. He has more help from science and technology, but he sometimes fails just as James Herriot did. Herriot’s boss Siegfried Farnon told him all those years before: no other profession gives you more chance to look like a fool. Or like a hero. Sometimes James Herriot did both several times in a single morning, as he drove from farm to farm in pre-war Yorkshire. Nearly a century later, Julian Norton is doing the same. And not just in the same county: in the same district of the same county. Norton is based in the Yorkshire town of Darrowby just as Herriot was and works for Herriot’s old practice.

Except that the town is really called Thirsk, not Darrowby. And Herriot’s boss was really called Donald Sinclair, not Siegfried Farnon. James Herriot himself was really called Alf Wight. The books he wrote under that pen-name weren’t journalistic but impressionistic: he edited events, combined characters and was sometimes writing short stories rather than strict biography. Julian Norton’s books aren’t like that: he’s often describing things that the TV cameras have already captured, so he sticks to facts and doesn’t resort to fiction. Apart from that, his books are a lot like the Herriot books. And particularly in the way that matters most: they’re fun to read. He doesn’t write quite as well as James Herriot, but you can learn more about animals from him. James Herriot dealt day in, day out, with a strictly limited set of four-footed patients: cows, sheep, pigs, horses, dogs, cats. He rarely treated anything else. Julian Norton routinely treats a much greater variety of animals than that: four-footed animals like alpacas, two-footed animals like swans, no-footed animals like snakes. And a lot more besides. I don’t want to see the TV series that inspired his books, but I’m glad that it did.